Chuck Ayers was a staff artist at the Akron Beacon Journal as well as doing the complete artwork on Crankshaft. He wasn’t that thrilled with life at the BJ, so I broached the idea of him leaving the paper and coming on board to pencil Funky along with his work on Crankshaft. I would still ink, letter the strip, and clean the studio as I had been as well as writing both Funky and Crankshaft. This would allow Chuck to leave the paper and, between the two of us, allow us to get a year ahead on both strips. Chuck agreed to do it. Contracts were drawn up and signed, and we got started. Chuck left the newspaper behind, and we hunkered down to work. It took us a little more than two years, but we were finally able to lap ourselves. So during the closing two years that this volume covers, we were essentially doing work that amounted to producing a third strip as well. The result was that the work would cease to be immediately topical, but it would begin to become pertinent (you’re probably wondering why that would be, because that’s the kind of inquisitive mind you have—allow me).

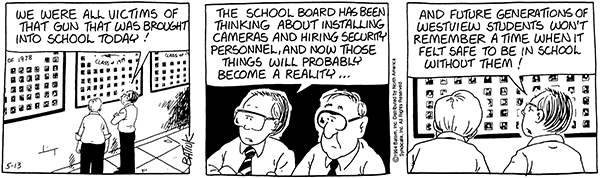

Aside from lifting the pressure of the short deadline that I had worked under for better than two decades, getting ahead for a year had another unforeseen salutary effect on the strip itself. No longer having to write something that had to be finished by the next Monday, my approach to the work began to change. I was able to begin to entertain long thoughts and to allow those thoughts to gestate for as long as they needed. My modus operandi in the past was to sit down to do some writing and to write as many ideas as I could in say an hour. This approach tends to limit you to gags and weeklong sitcom set pieces at best. Now I could sit down for an hour and not write anything at all, just blink and think. Slowly the work began to evolve toward much longer pieces that could eschew the easy gags that sit on the surface in favor of a more behavioral humor that arises from within the characters and the situations. Having the time that permitted me to approach more substantial work, coupled with Chuck’s artistic ability to do things I couldn’t do that the work needed done, I began to explore the possibilities of the medium in which I worked in ways that I’d not been able to do before. I had been tending this way with work like the teen pregnancy story, but the work was always on a very short leash because of the time constraints I faced. The first work of substance I tackled at that time was a small piece about a kid bringing a gun to school. It was something I had been working on as I was redlining the previous fall, and I returned to it I think as a way of proving to myself that I was back and firing on all cylinders. Not the best of reasons, and I’m afraid the work reflected it. I’m not happy with the way I’d handled it. It was a little too surfacy and lacked any real depth or development of either the characters or the situation. There was, however, one strip that caught my attention as I read it again for the first time in a long while. It was the May 13, 1994, strip where Fred Fairgood, the principal, is reflecting on the change that this incident of a gun being brought to a classroom would bring to his school. It’s sad to realize, in the twenty-four years since it appeared, how little distance we’ve traveled toward finding a solution to this pernicious problem.

From The Complete Funky Winkerbean Volume 8