The following article appeared in the 2022 Comic-Con International: San Diego Souvenir Book.

— by Maggie Thompson

After 30 years of co-editing Comics Buyer’s Guide, Maggie Thompson now writes online columns for Comic-Con International and Gemstone Publishing and maintains her website maggiethompson.com.

Tom Batiuk chose a sample strip and provided his own brief biography for The National Catoonists Society Album 1996.

Today’s comics fans might well wonder what went into making a strip that turned out to be destined to run for half a century—and is, yes, still running. Fans who have been around for a while might add what they’ve observed in the course of those decades: Newspapers and their comics pages have experienced an unending series of challenges. Such creators as Tom Batiuk have had to come up with accompanying strategies to solve problems.

Among his strategies has been a Funky Winkerbean website, and, in 2006, he provided an internet peek into his background for those looking for a brief summary:

“Okay, here we go, gang, biography lite. I was born in Akron, Ohio, in 1947. After graduating from Kent State University in 1969 with a bachelor of fine arts degree and a certificate in education I taught art in Elyria, Ohio, at Eastern Heights Jr. High.

“In 1970, while I was teaching, I began drawing a panel for the teen page of the Elyria Chronicle-Telegram. Those strips led to the creation of Funky Winkerbean in 1972. Funky is syndicated by King Features Syndicate to more than 400 newspapers nationwide. I skipped over a lot of hard work in the middle there, but that’s basically the gist of it for those of you doing term papers.”

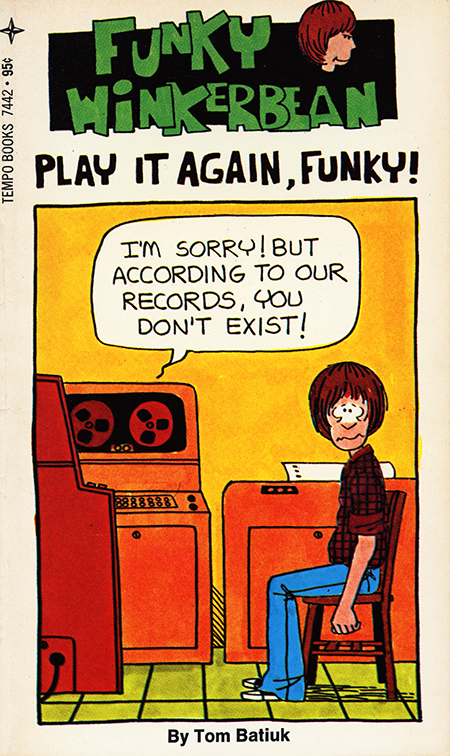

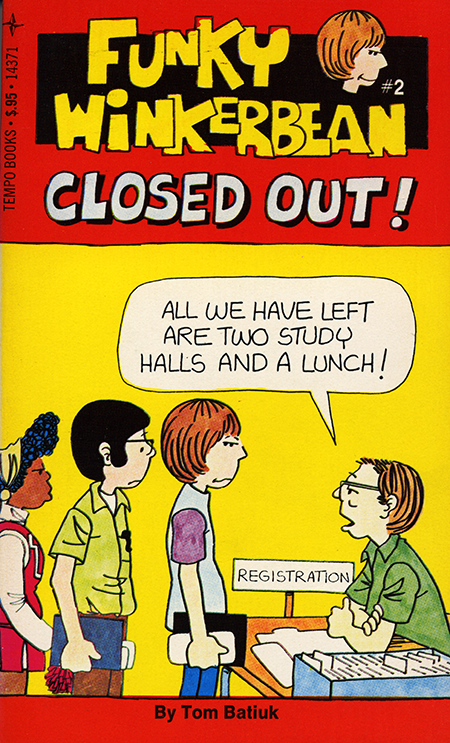

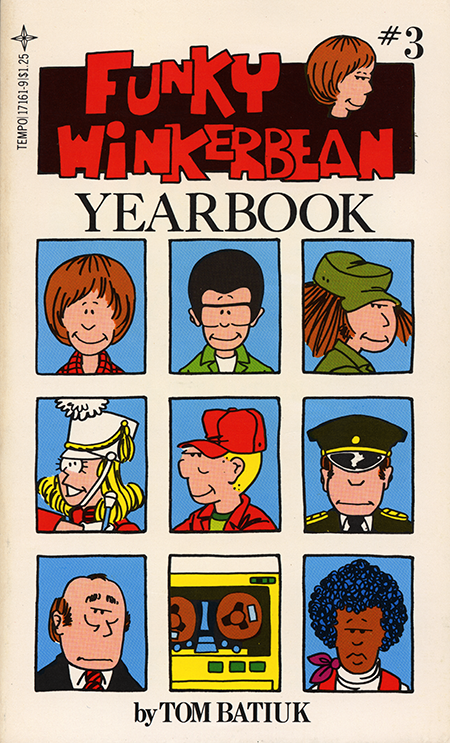

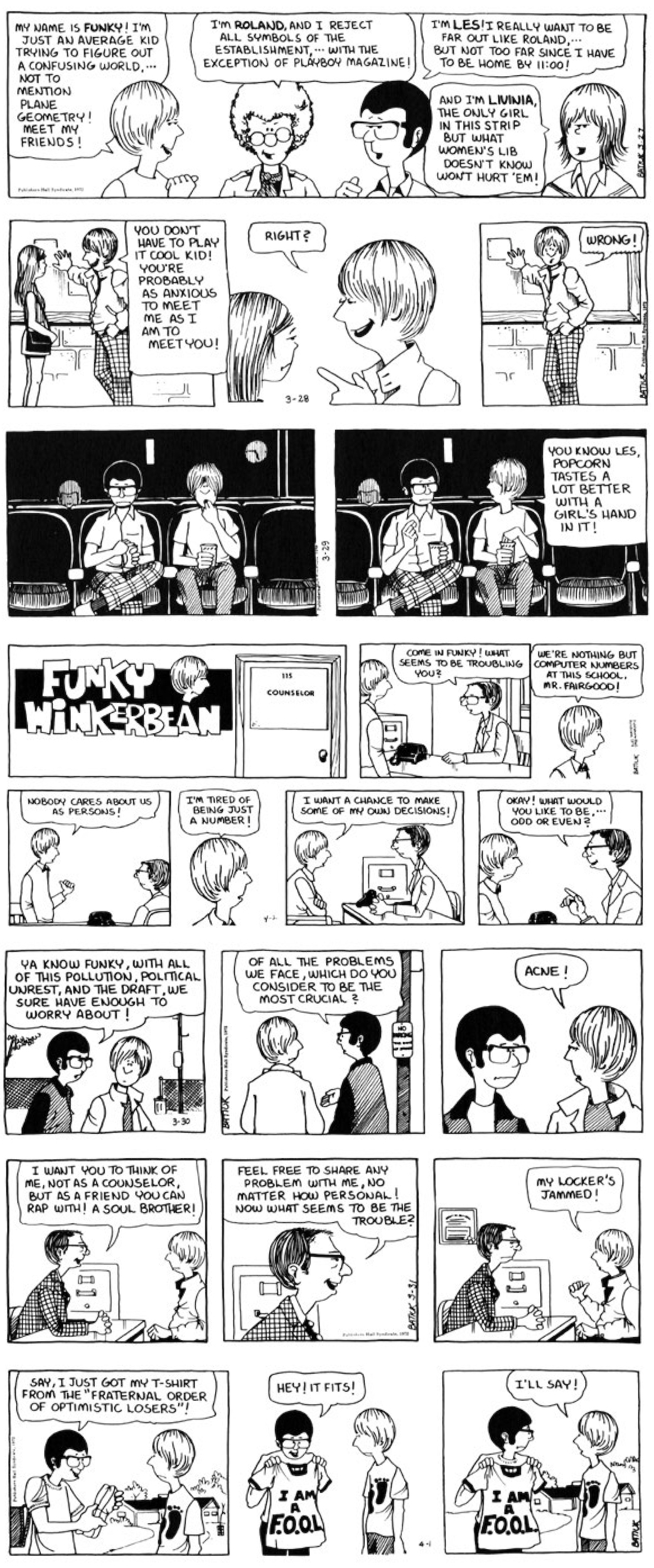

Early collections picked a focus and chose strips that worked in such stand-alone volumes.

“Funky’s just an average guy, trying to cope with high school, love, a summer job, and more than a little help from his friends…”

In the meantime, as he hinted then, there’s lots more to know. Lots.

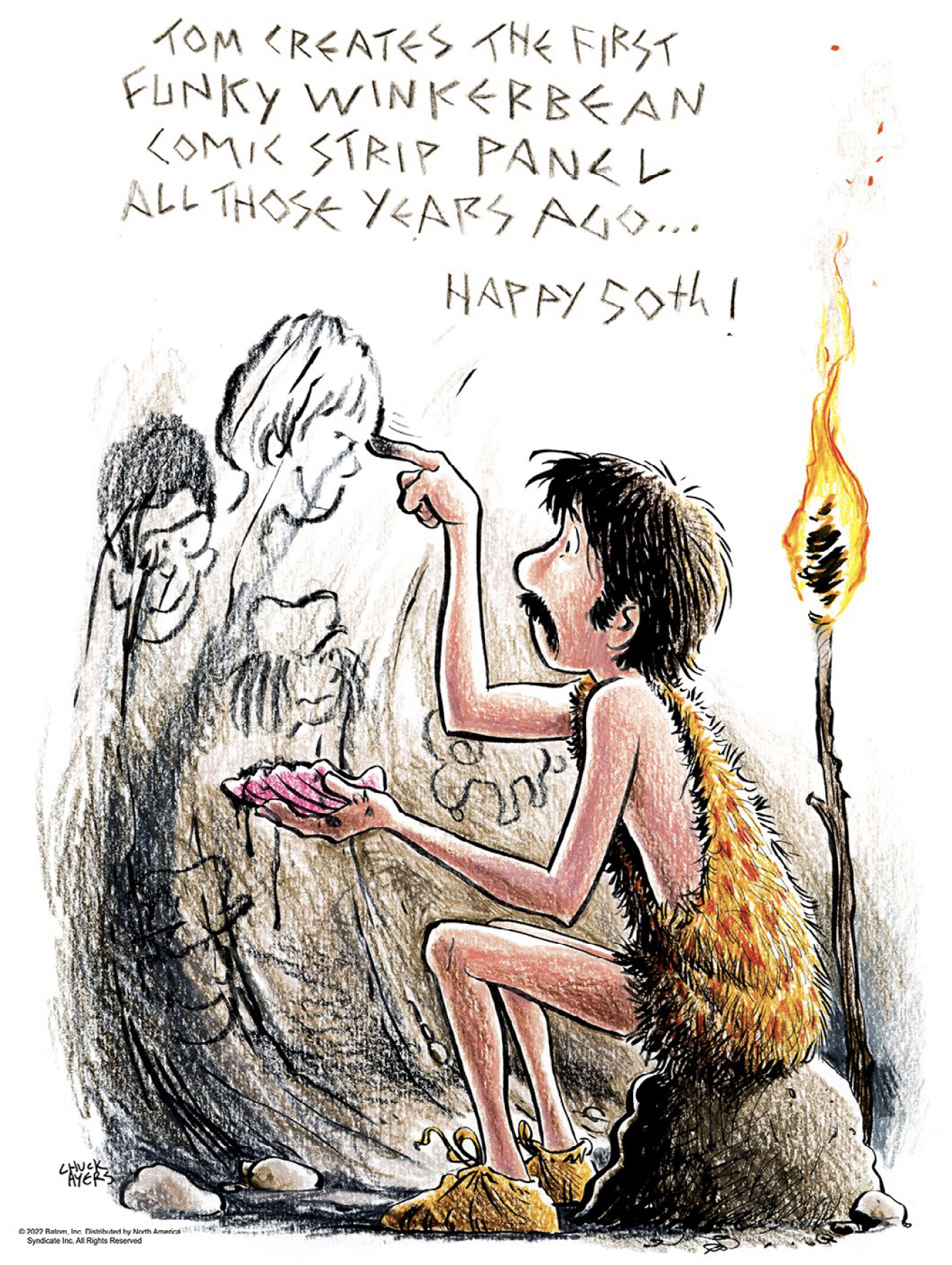

Looking back, consider the 2022 anniversaries: Tom Batiuk was born March 14, 1947; that’s 75 years ago. His Funky Winkerbean began March 27, 1972; that’s 50 years ago. [Initially, it was syndicated by Publishers-Hall (1972–1986), then by King Features/North America.] The spinoff Crankshaft strip began June 8, 1987; that’s 35 years ago. All of which is to note that there are many opportunities to celebrate this year.

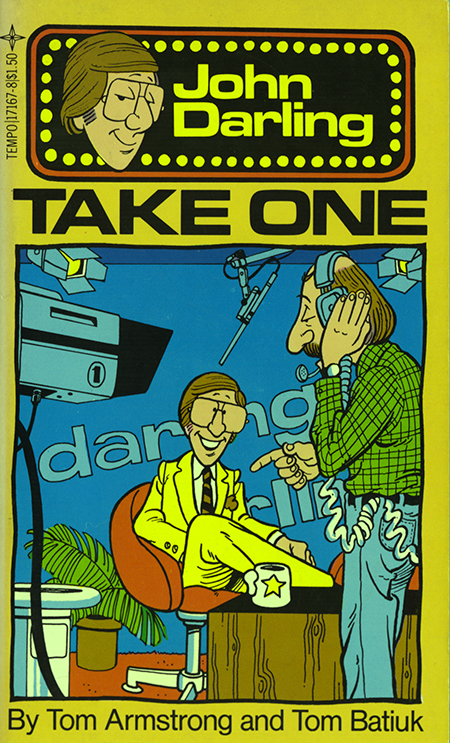

(To digress: fans of another Funky spinoff project will note that the John Darling strip ran from March 25, 1979 to August 4, 1990. But [spoiler!] it obviously didn’t last.) Oh, and long-time readers may remember that there were Funky time jumps in 30-years-ago 1992 and 15-years-ago 2007. We’ll get back to that, too.

If you were in junior high or high school in the spring of 1972, you were part of the Baby Boom or Gen X generation—and you were dealing with a vast variety of pressures and challenges. Because, let’s face it, you were in junior high or high school. And, if Funky Winkerbean was running in your daily newspaper and you were already enjoying the comics pages, chances are that you soon found kinship with one or more of the characters Batiuk was bringing to life.

Comic strips can be elusive in content and readership. They’re often taken for granted (and sometimes denigrated) by folks who see them in daily newspapers. And they’re often almost unknown to people who don’t get whichever daily newspaper carries the strip in question.

The Complete Funky Winkerbean: Volume 1, 1972-1974 brings readers the first week of the strip — and all the other installments throuh (yes) 1974.

Mind you, in the days of mass- market paperbacks on news-stand spinner racks, some strips received additional circulation (and potential for longer life) via reprints in that format. In 1975, three years after readers first met Funky, Les, and the others, a few of their strips showed up in newsstands in Funky Winkerbean: Play It Again, Funky! The first-page welcome to readers said, “Funky’s just an average guy, trying to cope with high school, love, a summer job, and more than a little help from his friends. They’re all here: Crazy Harry, Marcia and Jan, Les, The Coach, and many more. Add quips from a crazy computer and the wacky ‘wisdom’ of the ‘I Chong,’ and you’ve got Play It Again, Funky. Some-times hip, always hilarious—Funky’s fun for everybody!”

Following that and other small collections of excerpts came the trade paperbacks—in a larger size, more adapted to fitting on a bookshelf, but still consisting of focused selections. Nevertheless, in her foreword to the first Funky Winkerbean trade paperback (1984, subtitled “You Know You’ve Got Trouble When Your School Mascot Is a Scapegoat”), Erma Bombeck wrote that Batiuk was “more than a cartoonist”: “He chronicles probably one of the most difficult times of our lives . . . a time when our insecurities stand out like a piece of toilet tissue on our shoes . . . our apprehension grows daily and we are like children on a ferris wheel who would like to get off and be sick, but all the adults keep telling us what a good time we’re having.”

The back cover to that slim volume—published a dozen years after the strip had begun—identified the focal characters as Les, Holly, Crazy Harry, Mr. Dinkle, The Coach, and Funky, “The kid with the strangest name in the school.” And—as Bombeck indicated—the Funky Winkerbean strip itself focused on high school, high school, high school. Until it didn’t.

Since then, the “more than a cartoonist” Batiuk has provided insights about what made him that way. He and his strips have provided a variety of pop culture perspectives, as well as perspectives on the complications of life in general. That might have been because he had been so influenced himself by a variety of pop culture entertainments.

He told readers about it in the first of the hardcover series that started a decade ago. At that point, new fans could join long-time readers, thanks to the release by The Kent State University Press’s Black Squirrel Books of The Complete Funky Winkerbean Volume I 1972-1974. It came complete with a critical analysis by R. C. Harvey and an autobiographical introduction by Batiuk, who took readers new and old behind the scenes.

This and later volumes do, to be sure, contain fore-words from an assortment of commentators, each providing a personal view of the strip. But a major bonus is the addition of revealing autobiographical and analytical essays by Batiuk himself. Those provide insights into the world of comics creation and influences and what amounts to an analysis of the strip’s evolution over the decades.

For example, what readers in the earlier selected-strip collections would have guessed was that Batiuk was, himself, a comic book fan? Or knew about his first nationally published writing? (He was a fan of costumes and super-heroes and wanted to produce his own such stories. That first publication of his work was of his fan letter in DC’s The Flash #121 [June 1961]).

As he revealed in that first volume of complete Funky Winkerbean, the other pop culture experiences influencing him were many and varied.

Gene Autry in the 1935 Mascot 12-chapter movie serial The Phantom Empire? Yes, indeed—though he’d been born a dozen years after it first ran in theaters. “I became fascinated with the idea of taking what was considered to be a low art form and creating something of substance within those confines, of trying to take what others considered junk and turning it into something more. That thought continued to inform my cartooning choices for the next fifty years. It’s hard to overestimate the impact that The Phantom Empire has had on my developing brain.”

In 2022, the latest collection is released updating readers through the end of 2004: The Complete Funky Winkerbean: Volume 11, 2002-2004

He continued, “The clincher came when I got my hands on my first comic book.” It was Tom Corbett Space Cadet, presumably one of the Dell or Prize issues from 1952–1955.

And, of course, there have clearly been many other influences. One of the most popular characters coming from Batiuk’s own high school experiences was the band director, Mr. Dinkle. (People who experienced the real-world aspects of high school bands found many of them in Mr. Dinkle’s appearances. He was even featured in motivational posters aimed at music educators.)

Readers may have taken it for granted that such a popular character as the school-bus driver Crankshaft had been in the strip from the start, but Batiuk’s introduction to the fourth volume pointed out that he’d been added years later. “My normal method when developing a character is to take someone’s quirks and personality traits and exaggerate and expand upon them to create the character.” The inspirational bus driver he had known in real life was different. “In this case, I had to take the personality of my bus driver and tone it down quite a bit to make it believable enough for a comic strip.” He continued, “I immediately began hearing from readers who recognized that surly old curmudgeon. . . . Much like John Darling before him, Crankshaft was becoming a strip within a strip.” Not introduced until April 24, 1985, the bus driver earned his own continuity two years later in yet another strip.

These days? There are still newspapers, and Funky is still running, long beyond that character’s high school years. It is to be hoped that those who appreciate comic art are already supporting local newspapers that still carry comic strips—especially Funky Winkerbean.

Do pick up a copy of that introductory first volume to see both the foundation of the strip and Batiuk’s account of his motivations and creative inspirations. (If you hesitate initially to invest in your own copy, see whether your local library has one in its collection or can get it for you on interlibrary loan, if necessary.)

And, yes, you can orient yourself via online information, thanks to search engines. You’ll learn that Batiuk has worked with a number of collaborators on both the Funky strip and its spinoffs, credited online and in collections. Among those involved have been John Darling collaborators Tom Armstrong (1979–1985) and Gerry Shamray (1985–1990), and Crankshaft collaborators Chuck Ayers (1987–2017) and Dan Davis (2017–).

If the characters had aged in real time, Funky would be—what?—maybe 65. But Funky Winkerbean went from being frozen in time to two time jumps, and the characters are now in a designated “Act III.” Funky and the teens of “Act I” are now 46, and the adult Funky presides over Montoni’s restaurants in a variety of franchises. His 15-year-old son is Cory. Les Moore is the single parent (following the breast-cancer death of Lisa) of 15-year-old daughter Summer. Crazy Harry Klinghorn is also the parent of a 15-year-old daughter; her name is Maddie. And there are more, more, more in a diverse cast with changing relationships. It’s a cast that has dealt with losses as well as additions—and society’s challenges as well as its norms.

In his strips, Batiuk has provided perspectives on the complications of life: some merely annoying, some thought-provoking, some downright devastating. He tells readers without being preachy that they are not alone. His comic-strip characters have experienced challenges, have dealt with them, laughed about them, wept about them, celebrated them. And have often—though not invariably—survived them.

Anyone wanting to know more about Funky, Batiuk, the history of the strip itself, upcoming storylines, and/or more would do well to start the project by exploring https://www.funkywinkerbean.com. In any case, it’s a great time to celebrate the strip that has brought so much entertainment to so many. Here’s to Funky Winkerbean—and its variety. We’re lucky, indeed, to have so many ways to savor its Funky decades of insights. And laughs.

There’s another Funkyverse anniversary in 2022: Crankshaft is celebrating 35 years!