×

Subscribe to Receive the Latest Updates

Subscribe to receive our monthly newsletter.

Published November 17, 2014

By Brian Steinberg

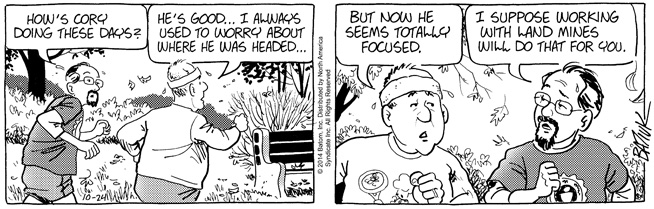

A woman searches fervently for a comic book to bring joy to her son, who is stationed with the military in Afghanistan. A man grapples with Hollywood producers over the script for a film that is supposed to be about his dead wife. Two middle-aged guys taking part in a charity race use the occasion to consider the inevitable: “You have to wonder how much longer we can keep running like this,” one says to the other.

Are you laughing yet?

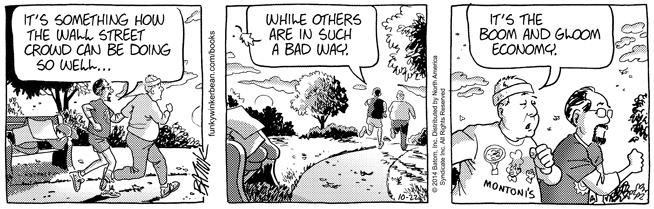

Haunting – some might say depressing – moments like these are the building blocks of a long running newspaper comic strip that these days acts like it’s something entirely different. For years, Tom Batiuk has studiously avoided the rut worn by Hi and Lois Flagston or Beetle Bailey and Sgt. Snorkel by experimenting with the format of his comic strip, “Funky Winkerbean.” Where other comics center on a small handful of characters, Batiuk manages a cast of dozens. Veteran funnies-page citizens like The Phantom and Dagwood Bumstead are lean and muscular, despite their advancing years. The title character of “Funky” (a reformed alcoholic, seen in the above picture, left) looks his age – paunchy and out of shape. Sometimes Batiuk’s three panels elicit a chuckle, but they often make a reader wince instead, as the title character and other citizens in his hometown of Westview fight breast cancer and racism. They don’t always win.

If Batiuk were to launch his comic with its current premise in today’s difficult economic climate for newspapers, “we would have an extra challenge,” says Brendan Burford, comics editor at King Features Syndicate, which sells the strip. Yet Batiuk has managed to keep “Funky Winkerbean” in about 400 newspapers for several years, he says, despite the tightening market for such stuff in an industry that is being rendered obsolete by new technology. Most newspapers, says Burford, would prefer something less demanding of readers. “’Just give me something that’s funny’” is the typical request.

Which is not what “Funky Winkerbean” offers. The cartoonist has “jumped time” twice over his forty-plus year tenure on the strip, forcing his cast to age very noticeably. Characters who once joshed about in high school now must ponder the vicissitudes of middle age and the sense they are moving into the back half of their lives. There are laughs to be had, but they are just one element of a recipe that delivers one short story after another about people just trying to make it from day to day. In that sense, “Funky Winkerbean” has become something akin to Sherwood Anderson’s short-story collection “Winesburg, Ohio,” about a group of people trying to stave off loneliness and isolation in a small town, or William Saroyan’s “Human Comedy,” which examines the ups and downs of the populace of the fictional town of Ithaca, California. It’s the kind of stuff we could envision the “Peanuts” characters taking on, had they been allowed to advance to middle age.

“I found writing about adult relationships much more nuanced, much more complicated,” says Batiuk, who invokes everyone from philosopher Emmanuel Kant to super-hero Green Lantern during a wide-ranging discussion. Had he hewed to the comic’s original premise, “it would have become like other teen strips – dated and outmoded. That was always in the back of my mind. I wanted to avoid that pitfall.”

To get there, he has had to devise non-traditional working patterns. He writes “Funky Winkerbean” strips about a year ahead of the when they are slated to publish, the better to craft longer-term plotlines. The process, he says, took him about two and a half years: He created extra two-week or three-week batches of the strip to build a time cushion “It has really benefited the strip, because all of a sudden I could think long thoughts and I could let a story gestate for a long time in my head – before I had to even worry about putting something down on paper,” he says.

Batiuk isn’t the first funnies-page resident to tinker with the milieu’s old model. Lynn Johnston let her characters age in real time in “For Better or For Worse,” which started as another family-comedy strip and progressed into a chronicle of a maturing young family and the life surprises they encounter. Garry Trudeau’s “Doonesbury” has long zipped among tens of characters, some of them the children of the strip’s original cast. “Gasoline Alley” still features original characters Walt Wallet and his adopted son Skeezix, even though both are senior citizens.

Yet the artist’s work progresses as newspaper comic strips, many of which date back to the 1930s (“Blondie”), 1950s (“Beetle Bailey”) or 1960s (“Apartment 3-G”) seem particularly out of sync with a consumer base that gets more of its information and entertainment from digital sources and likes to immerse with a favored piece of content more than three panels at a time.

Indeed, one might liken Batiuk’s work to what is taking place currently on television, where some of the medium’s best-loved programs feature finely etched characters and flawed protagonists attempting to move forward despite difficult conditions – a zombie apocalypse, say – with little guarantee of success. Consider Funky Winkerbean, a pizza owner on his second marriage who has a strained relationship with his son, or Les Moore, a nebbishy widower trying to keep his new wife happy while remaining devoted to the memory of his first. This could be the funnies-page take of the characters from NBC’s “Parenthood,” maybe.

Tom Batiuk, 67 years old, has had a fascination with the comics from a very early age. “When I lived back in Akron, my dad would read the comics to me. I could just tell there was something powerful going on.” After graduating from Kent State in 1969, he visited both DC Comics and Marvel, the two big super-hero publishers, in hopes of gaining a job. Editors at both houses told him he was too green. After getting a job teaching arts and crafts at a junior high school,. Batiuk managed to get work for the Elyria, Ohio, Chronicle Telegram, contributing a cartoon to a page the paper ran for teens on Tuesdays. Things developed from there. “Funky Winkerbean” would debut in 1972

The cartoonist says he has tried to steer his comic in a more serious direction from its earliest days, even visiting a high school to gain more realistic detail. “I was repackaging a dated genre – the ‘Archies’ and ‘The Jackson Twins,’ ‘Ponytail.’ Teen strips were getting long in the tooth,” he says. “I wanted mine to be different, to be about today, to have that attitude.”

Early attempts to walk the edge were met with resistance, he recalls. Batiuk once worked up a series about teen pregnancy, only to be told by his syndicate bosses that such stuff would not play. “They basically said, ‘There’s nothing in the newspaper like this and it’s going to stay that way, ‘” he recalls. “Without having editorial control over my work, I was hamstrung. What I did was nudge the strip in little ways. I started moving from a gag a day to more of a sitcom situation, a longer form story. I would try to get into more adult things, like a coach having a heart attack. And once I had gone through some of the surface jokes, I started digging a little bit, getting into how you start making contracts with God, ‘If you get me out of this one….’ A little deeper. A little bit more substance.”

Editorial control came after 1984, when “Funky” became part of Rupert Murdoch’s News America unit. “I immediately dusted off the first series on teen pregnancy,” Batiuk remembers. In that arc, a teen girl named Lisa discovers she is pregnant. The nerdy Les Moore (seen at right in the top photo)“became her best friend and companion, even her Lamaze partner,” says Batiuk. “It became awkward to take him from a more mature position back to hanging on the gym class rope and being afraid to climb down.”

Next, Batiuk tried something even more radical. In 1992, he restructured the strip, moving his characters out of high school and into a situation where they began to age as the strip moved along. “Funky Winkerbean” became more of a drama than a comedy. By 2006 and 2007, he had gained notice for putting one character – the “Lisa” who had gotten pregnant as a teen – through a horrific cancer ordeal, which, ultimately, she did not survive. And then in October of 2007, he accelerated the comic again, jumping everything ten years ahead.

Following his own muse has roused a fervent following for Batiuk, says Burford, the editor. “Funky” has “become an untouchable comic strip,” even if its creator “does do work that’s different from the other comics on the comics page.”

Over the years, Batiuk has attempted more off-kilter antics. Between 1979 and 1991, he wrote another comic, “John Darling,” about a buffoonish talk show host originally introduced in the panels of “Funky.” In the second-to-last episode of “John Darling,” the title character was assassinated – the better to keep his intellectual property from being used by others, says Batiuk. He also maintains a strange connection between “Funky” and another comic he writes, “Crankshaft,” about a grumpy older gentleman. The two strips sometimes cross over, but complexity reigns when they do. After all, when Batiuk set “Funky Winkerbean” ten years, “Crankshaft” remained hitched to its original moment in time. When “Crankshaft” characters appear in “Funky” panels, they are a decade older (and the senior-citizen protagonist is stuck in a home for the elderly, unable to care for himself). Where else in the comics can readers get a glance of a where a character is ultimately headed? “It takes a little thought, but it can be done,” says Batiuk.

These ideas, the cartoonist says, “bring people back every day” in a way that a daily joke may not. “Your jobs is to chase your characters up a tree and then throw rocks at them every day,” he says, and the reader’s curiosity about discovering how things will end can form a more powerful lure than humor.

The current trajectory of the newspaper business may lend Batiuk some of his freedom. Simply put, the consumption patterns of funnies-page aficionados are in flux, and whether the numbers of people who examine the comics digitally make up for those who no longer read them in their paper-and-ink home remains to be seen. Batiuk sees small-town newspapers thriving in ways their big-city counterparts may not. “If that’s the case, there will still be comic strips, but boy, it’s going to get even tighter and tighter in terms of competition,” he says.

Meantime, he keeps plotting. In January, “Funky” characters are slated to meet Dick Tracy, who is published by a different syndicate, the result of a meeting with “Dick Tracy” artist Joe Staton at a comics convention. “That’s just fun for me,” says Batiuk. Yet the crossover, involving characters from comics distributed by two different companies, is the equivalent of having Marvel’s Captain America team up with DC Comics’ Swamp Thing.

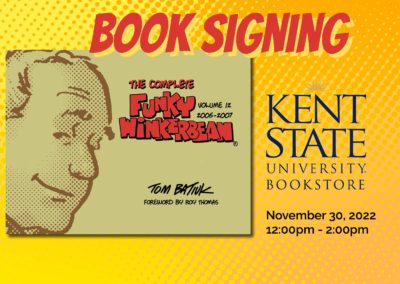

Batiuk isn’t necessarily interested in getting a Taylor Swift-sized readership for his cast of characters, but certainly wants to keep things interesting for the strip’s die-hards. He recalls doing a recent book-signing at a local library in southern Ohio, near his stomping grounds. “There was a lot of gray hair out there,” he recalls, “and I thought, ‘This is the ‘Funky’ gang, and they’re still here.’”